Raspberry Pi + Arch Linux ARM + bcache + iSCSI + LVM cache + VDO + KVM + ZFS

Yep, that’s how mad I’ve got during this lockdown.

What gave the idea

About two months ago, an update to the Raspberry Pi OS (ex Raspbian) added Microsoft’s VS Code package repository and its corresponding GPG key to the system. There’s discussion about it over at r/linux (tread lightly in the comment section). While I don’t mind Microsoft’s products - I think VS Code is great -, what I do mind is the Raspberry Pi Foundation slowly adding more and more “bloat” to the OS that affect storage capacity, network use and resource consumption in general. They’re turning the Raspberry Pi into a small desktop computer (hell, Raspberry Pi OS is available for standard x86-based desktops), whereas I’m more into the tiny Linux-based embedded ARM computer. Our interests are diverging, so at that point I decided the best course is to pick another OS to run on my… too many Raspberry Pis.

Time to pick a new OS

The usual options for a standard Linux distro on ARM are, but not limited to, Ubuntu, Debian, OpenSUSE and Arch. Ubuntu on the server is just… no, and while I’m a fan of bare Debian, the Raspberry Pi OS is still Debian-based itself so it would’ve been quite boring. I’ve never used OpenSUSE, so I’d rather not jump blind into a new environment. That leaves Arch, which while officially doesn’t support ARM, there is a third-party port called Arch Linux ARM that is well-supported and active. It has documented support for all the Pis, runs well in them despite the architectural differences, and I’m mad enough to already know Arch well. First step into madness: running Arch on a bunch of Pis.

eugh. SD cards.

so. SD cards. I have many (too many?) Raspberry Pis so I’m not very thrilled about having to get and maintain that many SD cards. They’re not very durable overall, and while the small ones are cheap enough, I don’t feel like going around buying and replacing 16 gig SD cards at minimum. Second step into madness: running the Pis without any onboard storage. I want to have a single machine that contains the boot and root filesystems for each Pi. They’d all boot off their own respective boot filesystems with TFTP, and then mount the root filesystems with NFS.

Roots and boots

I have a repurposed old desktop PC running Proxmox. It has an SSD for storing VMs and a couple of HDDs for bulk storage. It uses ZFS for all these.

psst, this covers the KVM + ZFS bit in the title!

I created a new CentOS 8 VM in there, which lives in the SSD but has a couple hundred gigabytes of bulk storage from the HDDs. In this bulk storage I created an XFS partition, since it supports reflinking - think filesystem-level deduplication.

Since the bulk storage is going to contain multiple almost identical root and boot filesystems, it only makes sense to use some sort of deduplication. It should achieve large space savings, since each unique block of data is only stored once. Any copies are then just linked to it, so while the filesystems are all separate, a large portion of their data is stored only once. Theoretically, in my situation, it should achieve over 90% space saving.

These boot filesystems are shared over both TFTP and NFS, and the root filesystems over NFS. Simple stuff.

Booting a Pi off the network..?

The network boot scenario is very common in the IT world - if you use x86. Like all booting, network booting happens in the device’s firmware, which is easy enough with an x86 board and BIOS/UEFI. The Raspberry Pi firmware does in fact support network booting. Too bad it’s janky as fuck.

The usual process for network booting a machine off the network is about as follows;

- The firmware initialises itself, then initialises itself a network interface.

- It gets itself an address with DHCP. In addition to the address information, it gets the address for the network boot server, and possibly the name of the boot file. Otherwise it’ll derive a name for the file based on its network interface’s MAC address.

- It requests the boot file with TFTP from the boot server. If no boot server was specified, it likely uses the address of the DHCP server.

- This boot file contains enough information and procedure to continue booting, such as downloading the kernel image from the boot server and possible configuration for it. From this point onwards it’s no different to using a normal local boot filesystem, except of course the filesystem living elsewhere.

But what’s so janky about the Raspberry Pi then? It does support this same process, however it deviates in steps 2 and 3: it does not use the supplied boot server at all. It always tries to use the DHCP server.

Not really that much of a problem.. if you’re a consumer who read a tutorial online on how to run dnsmasq somewhere, such as another Pi, to replace your consumer router’s crappy DHCP server. My setup is a bit beefier however, so replacing the router’s DHCP server with dnsmasq running somewhere really is not an option. Since my router is a Mikrotik, and it runs RouterOS, it has a built-in TFTP server as well. It would work, except the Pi has to be able to update the boot files whenever its bootloader and/or kernel update. With RouterOS it’d probably have to happen with SMB of all things, and I am not updating them by hand. So that’s not an option either.

I toyed around with the idea of separating the Pis into their own little network segment where there would be a separate DHCP server that serves the boot filesystem both over TFTP for when the Pis are booting, and over NFS for when the Pis are booted and have to make changes to them. This would’ve worked well, but then I realised I have a bunch of Pi Zero W’s that don’t support network booting at all. I use the Zero W’s to run some sensors and LED strips - more on that later maybe? There’s no way to bake wireless credentials into the Pi firmware so even if it would manage to initialise the wireless interface, it wouldn’t be able to connect to any network.

Fuck network booting then

So I can’t get away with having an SD card in each Pi. What’s the next best thing though?

Boot the Pis from the SD card normally, but still mount their root filesystems over NFS. This allows the Pis have only teensy SD cards - only big enough to contain the ~500 megabyte boot partition - while their actual root partitions over the network can be a lot larger, 16 gigabytes in my case. I ended up getting some cheap-af eight gigabyte SD cards, since any smaller don’t seem to exist anymore.

Booting Arch with its root in NFS is well-supported in its initcpio tooling, so that bit wasn’t really anything special. What is special, however, is making it work with the wireless Zero W.

Wireless in the initial boot environment

Mounting an NFS filesystem requires a network connection. Having a wireless network connection means initialising the network adapter, and connecting to a wireless network. This means baking the wireless adapter kernel modules, wpa_supplicant, the network credentials and a hook to initialise it all into the initial RAM filesystem. Sounds easy enough!

The Zero W wireless chip requires some kernel modules, and a couple of firmware blobs and configuration files to operate. In an Arch mkinitcpio.conf file, these would be:

MODULES=(brcmfmac brcmutil cfg80211 rfkill)

FILES=(/usr/lib/firmware/brcm/brcmfmac43430-sdio.txt /usr/lib/firmware/brcm/brcmfmac43430-sdio.bin /usr/lib/firmware/brcm/brcmfmac43430-sdio.clm_blob)

The files and modules are the same across distros.

There’s a helpful hook package in the AUR that bakes wpa_supplicant and wireless credentials into the init RAM filesystem and runs it with the wifi-hook. Afterwards, the net-hook can be used to configure the interface with an IP address. There’s a catch in the wireless hook though; in its cleanup stage, it kills the wpa_supplicant daemon, effectively killing the wireless connection. NFS doesn’t like this. A simple workaround for it is to disable the cleanup hook by deleting it completely, adding a return 1 to its first line, or what have you. This’ll leave the wpa_supplicant daemon running, even after the actual system boots.

Since the network adapter comes pre-configured with an address from the init environment, it’s important to tell your network configuration tool to just accept the existence of the existing address. In my case it was a simple KeepConfiguration=true in systemd-networkd’s interface configuration.

Sidenote; leaving processes running isn’t exactly good hygiene for an init RAM environment. Any processes it leaves running won’t be managed by the actual system’s init process, so it’s easy to run into trouble with resource contention or process crashes. But hey, NFS works!

What about the largely empty SD card?

If you recall the post title, so far we’ve got “Raspberry Pi + Arch Linux ARM + NFS + KVM + ZFS”, which is quite far away from the madness still left in there.

Since I’m using eight gigabyte SD cards, about half a gigabyte is for the boot partition and two gigabytes for swap, it still leaves over half of the SD card unused. Good space for some caching, right?

Yeah, except filesystem caching to a dedicated block device is.. well, it’s not really that much of a thing. Linux of course caches filesystem activity into memory, but it won’t touch swap with this cache. The usual thing done with two stacked filesystems is to use an overlay filesystem with them, but this isn’t quite what I want here. In an overlay filesystem, the underlying filesystem is a read-only “base”, on top of which a read-write filesystem is, well, overlaid. My scenario is to have the NFS filesystem be the read-write base, and the empty space in the SD card used for primarily write caching. No matter which way the overlay filesystem is applied, it wouldn’t achieve this.

But wait, block level caching is much more common! There are standard solutions to it, such as LVM caching and bcache! It’d also mean requiring block-level access to the networked root filesystem - easy enough with iSCSI!

Sidenote; anyone who thinks iSCSI is “easy enough” should reconsider their life choices.

Rebuild the root

Since the scenario changed NFS over to iSCSI, it means rebuilding the method of sharing the root filesystems. I ditched the single XFS filesystem, which also means I lost the deduplication. Not to worry; since I’m using CentOS 8, there’s VDO available out-of-the-box that lets me create a virtual block device with block-level deduplication and compression.

Sidenote; ZFS, which I’m using in the hypervisor, also supports both these things. But ZFS is much worse in terms of deduplication - ZFS’s deduplication eats a lot of resources just by existing, so with this hardware it’s not an option. Its block compression is easy and largely transparent though, so I’ve had it active all this time.

I created a new VDO device directly into the bulk storage and enabled only deduplication. Since the underlying ZFS is compressed, compressing blocks here wouldn’t have any effect and just waste CPU time. Out of this new VDO device I created an LVM physical volume, and with it a new LVM volume group. Then I had the idea of using the SSD space as caching, since LVM supports that easily as well. Ah well, I’m pretty deep into the madness so why not take a few more steps. Expand the SSD volume a bit, add a new LVM physical volume, stick it into the new volume group.

Into this volume group I created a good bunch of logical volumes, each stored in the HDD and write-cached via the SSD. Into these I created new ext4 partitions and slapped some fresh Arch Linux ARMs in ‘em. And finally, shared them with iSCSI using the newfangled targetcli.

For mostly laughs, I checked how well the VDO device is deduplicating eight identical filesystems - 97%.

So booting off iSCSI it is then

Running Arch on an NFS root is easy and well-documented. The same thing but with iSCSI though, not so much. The Arch wiki has an article about it, but at the time it was so terribly written I got physically angry just by reading it. Guess I gotta figure it all out myself then.

Sidenote; I’ve since then rewritten the entire article myself based on my experiences with this madness, added some more information to it and just overall made it clearer and conform to the Arch wiki guidelines. It’s over here.

The standard iSCSI tooling for Linux is Open-iSCSI. Its userland tools are essentially split into three: iscsid, iscsiadm and iscsistart. The first two are for running and managing iSCSI sessions. The daemon handles the sessions in the kernel and overall keeps them running. iscsiadm is then used to manage these sessions. The third one, however, is meant to be a one-shot just-get-a-session-open-and-forget-about-it, which is exactly what you do in the init RAM environment when mounting a root partition over iSCSI.

iSCSI initcpio hook

Similarly to how wireless was handled earlier, iSCSI is handled with an initcpio hook as well. The hook starts the iSCSI session with some given parameters, then leaves it in the kernel. Later when the actual system boots and the iSCSI daemon starts, it’ll detect this session and “takes it over” for itself, so the session isn’t left unmanaged.

The hook’s installer adds the required kernel modules into the init RAM filesystem image, and the iscsistart binary. The hook itself simply runs iscsistart with preset parameters. Since there’s no iSCSI daemon in the init RAM filesystem (and you shouldn’t put one in there anyways), all the parameters have to be baked in to the hook.

/etc/initcpio/install/iscsi

build ()

{

local mod

for mod in iscsi_tcp libiscsi libiscsi_tcp scsi_transport_iscsi crc32c; do

add_module "$mod"

done

add_checked_modules "/drivers/net"

add_binary iscsistart

add_runscript

}

help ()

{

cat <<HELPEOF

This hook allows you to boot from an iSCSI target.

HELPEOF

}

/etc/initcpio/hooks/iscsi

run_hook ()

{

msg "Mounting iSCSI target"

iscsistart -i iqn.2021-03.initiator:name -t iqn.2021-03.target:name -g 1 -a PORTAL_ADDRESS -d 1

}

And that’s that! A Raspberry Pi running off an iSCSI root! Just ensure it never loses network connectivity, or else demons ensue.

You forgot the SD card again…

Right, yeah, the SD card is still largely empty. But not to worry, block caching is much easier than filesystem caching! The two options for it here are really LVM caching or bcache, so I opted for bcache since I’m already using LVM cache in the iSCSI target system.

Setting up bcache requires constructing a new bcache device out of a backing assumed-slow storage, and a caching assumed-fast storage. I created an empty partition in the SD card, but I had to wipe the filesystem in the iSCSI target in order to put bcache in its place. eh, whatever fine. Once the new bcache device was in place and a new filesystem stuffed into it, booting with it was surprisingly straight-forward. Once the kernel gets the iSCSI device open, the bcache module kicks in and creates the special bcache block device, and the kernel can then use it as a root device.

Final words before I go completely mad

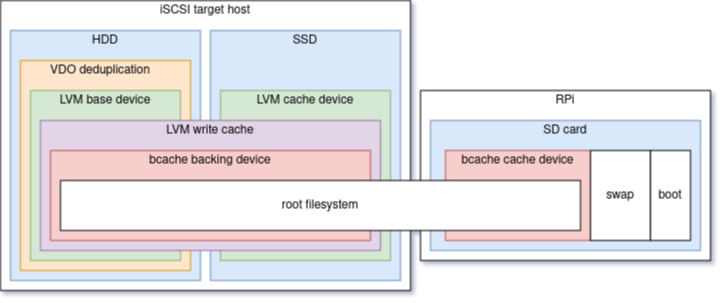

Since everyone loves diagrams and pictures and whatnot, here’s a sort-of diagram on how the whole setup is built, not including the KVM host because I couldn’t figure out a nice way to display it. Just take my word there’s an SSD and two HDDs underlying the respective drives.

While this article may seem quite straightforward, all in all this process spanned (pun intended) over a month or so, debugging weird issues and trying to get all the bits and pieces into place. A lot of alcohol was spent. And even now, it’s not perfect. iSCSI over a wireless connection in the init RAM environment isn’t that great of an idea (who would’ve fucking thought?) and just outright doesn’t work. Still haven’t figured out why. I have a hunch it’s about the wireless interface’s MTU though.

Speaking of the init RAM filesystem, and as I mentioned earlier, the wpa_supplicant is left running when the actual system boots which is something I should figure out. Maybe have systemd take it over somehow I dunno? Anyways, these two issues should probably get fixed in one go, since they’re what’s holding me back from running Zero W’s with iSCSI’d and bcache’d roots. But normal Pis work fine!

Anything good come out of it?

I admit, all of this was largely for the sake of being able to do it. The whole “bunch of Pis with their roots in one place” is a neat side-effect, but I’ll leave it as an excercise to the reader to figure out if it’s really worth it over just running the Pis normally off their SD cards.

But hey, I did end up rewriting the terrible iSCSI boot article in the Arch wiki, so that’s something!