Using Traefik's Let's Encrypt DNS challenge in a network with DNS redirection

Skip to the very bottom of the page to see a possible solution, or keep on reading for an explanation what might be wrong.

I’m using Traefik as a reverse-proxy for several services in an internal network. I want valid TLS certificates from Let’s Encrypt for these services, and since access to the network is blocked from the outside, the possible ACME challenge is dns-01. The challenge, in essence, generates a token that you have to insert into a public DNS TXT-record that the ACME provider will use to ensure that you own the domain you’re requesting a certificate for. However, due to how Traefik - actually the library Traefik uses, lego - the challenge doesn’t work as-is in a network with redirected outgoing DNS.

I ran into this issue myself and couldn’t find any straightfoward information online why, so now I’ll explain why it happens and how to fix it, just in case someone else runs into it as well. Hopefully this post has enough keywords to show up in search engines.

Redirected outgoing DNS

DNS queries by themselves are not encrypted at all. There is DNSSEC, sure, to sign and validate records, but many zones still do not use it, nor do many clients not enforce it. In order to secure DNS traffic, it has to be encrypted. There are several solutions nowadays, but I’ll be focusing on DoT - DNS-over-TLS. As the name suggests it’s simple; instead of sending DNS over plaintext, first a TLS connection is established with the resolver and the query is sent over that connection. Clients can choose to use DoT themselves, but it is also possible to force an entire network to only use DoT for outgoing queries.

Networks often have two (or more) local DNS resolvers that all clients (should) use. They can sometimes host a local authoritative zone for that network for local records, but most importantly they either resolve incoming queries themselves using the DNS lookup process, or by forwarding the query to some other resolver.

Local resolvers

My internal network has two local resolvers. I’m using PowerDNS Recursor and dnsdist for them, such that Recursor listens on :53, provides the local zone and some other functionality, and forwards all other queries to dnsdist running alongside it. dnsdist simply forwards the queries to Cloudflare’s 1.1.1.1 and Google’s 8.8.8.8 via DoT.

Recursor:

...

recursor:

forward_zones_recurse:

- zone: . # match all zones

recurse: true

forwarders: ["127.0.0.1:553"]

And dnsdist:

-- listen on public interface to allow clients bypass recursor running on :53 if needed

addLocal("0.0.0.0:553")

newServer({address="1.1.1.1:853", tls="openssl", subjectName="one.one.one.one", validateCertificates=true})

newServer({address="8.8.8.8:853", tls="openssl", subjectName="dns.google", validateCertificates=true})

This way, when clients send unencrypted queries to the local resolver, they will be forwarded to the external resolvers encrypted. However, it is still possible for clients to just not use the local resolvers at all and send out unencrypted queries themselves. This can be mitigated with the local router/firewall by redirecting all outgoing DNS queries to the resolvers.

DNS redirect and hairpin NAT

In the network’s router, it is possible to create a NAT rule that redirects all outgoing DNS queries to the local resolvers. Alongside it is also required to create a so-called hairpin NAT rule to “complete” the redirection to prevent an issue with the redirection.

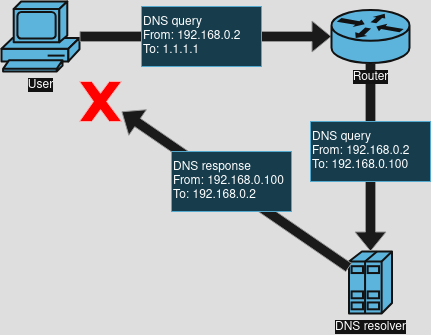

This is what happens with just the redirection rule, without the hairpin rule. The user sends a DNS query to some external DNS resolver, and it traverses through the router. The router’s NAT rule rewrites the destination address to the local resolver and forwards the query there. The resolver receives it and responds directly to the user, but the user will reject the response since it expects the response to arrive from the external resolver, not the local resolver.

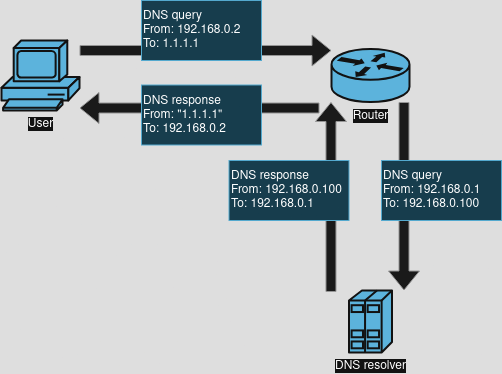

The hairpin NAT rule additionally masquerades the source address of the query as well to the router, and “fakes” the source address for the returning response. Like before, the user sends a DNS query to some external DNS resolver, but now the router changes both the destination and source address of the query. The new destination is the local resolver, and the new source is the router itself. Once the resolver responds to the router, it changes the response’s destination address to the user and the source address to the address that was originally masqueraded, in this case the external resolver’s address. It essentially fakes being the external resolver while forwarding all queries to the local resolver.

My network uses a Mikrotik router and its corresponding NAT rules look as such. Mikrotik’s RouterOS firewall is basically a glorified UI for Linux’s netfilter, so it should be fairly straight-forward to translate these rules for your router/firewall.

;;; hairpin NAT on LAN

chain=srcnat action=masquerade src-address-list=LAN out-interface-list=LAN

;;; force UDP DNS queries from LAN to local resolvers

chain=dstnat action=dst-nat to-addresses=10.40.0.2/31 to-ports=53 protocol=udp src-address-list=LAN dst-address-list=!PRIVATE dst-port=53

;;; force TCP DNS queries from LAN to local resolvers

chain=dstnat action=dst-nat to-addresses=10.40.0.2/31 to-ports=53 protocol=tcp src-address-list=LAN dst-address-list=!PRIVATE dst-port=53

Why this can break ACME

The ACME protocol is what services such as Let’s Encrypt use to offer fully automated globally trusted TLS certificates. I won’t be going deep into how it works, but on very simplified level it works as such:

- An CME client contacts an ACME certificate authority (CA) to request a certificate for a domain and requests to use some challenge.

- The CA responds with whatever the challenge requires that the client has to complete in order to prove it controls the domain it’s requesting a certificate for.

- The client completes the challenge and the CA issues a new signed certificate for the client for the domain(s) it asked for.

The usual challenge is https-01/tls-01, which requires the device that is requesting the certificate be publicly available on the internet on TCP port 443. However I’ll be focusing on the dns-01 challenge specifically, since it allows requesting certificates for a device that isn’t publicly available.

The dns-01 challenge works roughly as such:

- The client contacts the CA to request a certificate for a domain and requests to use the dns-01 challenge.

- The CA responds with a nonce value that the client should insert into public DNS for that domain with some method.

- The specific DNS record it should create is a TXT record called

_acme-challenge.<domain>, for example requesting a certificate forexample.commeans creating a TXT record called_acme-challenge.example.com.

- The specific DNS record it should create is a TXT record called

- Once the record is inserted, the client notifies the CA that it is ready.

- Many clients at this point wait and check that the record has propagated properly before notifying the CA.

- The CA queries the record itself and if it matches the nonce, it can then issue the certificate since it knows that client is in control of the domain it requested a certificate for.

Since many DNS providers have APIs for controlling DNS zones, this entire process can and should be 100% automated.

Traefik and lego

The crucial part is step 3.1 from above: waiting for the record to propagate before proceeding. Many ACME clients have a simple process for it; simply keep querying DNS for the newly created record to propagate. In a network with redirected outgoing DNS this isn’t an issue, because the queries are just normal DNS queries and since the zone being queried is public, it can be queried normally.

However, Traefik/lego does something different.

- Create the TXT record in public DNS.

- Query local DNS for the domain’s zone’s authoritative nameservers.

- Query the nameservers directly, without recursion, until they respond with the record, showing it has propagated.

- Once the record has propagated, continue.

Notice the issue here? In step 3, when the nameservers are queried directly, in a network with redirected DNS, the network’s router/firewall instead redirects those queries to the local resolvers. Since Traefik/lego is querying the nameservers directly, it doesn’t expect them to recurse to get an answer so it sets the no-recurse bit in the query. When the local resolvers receive a query without the bit set, and it’s not for a zone they’re authoritative for, they go “¯\_(ツ)_/¯” and respond with REFUSED. You can simulate this behaviour with dig, for example:

dig example.com @1.1.1.1 +norecurse

Since Traefik/lego keeps receiving REFUSED for the query, it keeps retrying until finally timing out and canceling the ACME process. Luckily the fix for this is simple. Traefik has some options available to control the DNS propagation process, namely propagation.disableChecks and propagation.delayBeforeChecks. The former option disables the propagation checking entirely, but it comes with a caveat: it will notify the ACME CA that the DNS record is ready immediately after creating it, which very likely isn’t enough time for it to propagate. The latter option adds a delay to this, which allows some time for the record to hopefully propagate. In Traefik’s configuration it looks something like this:

...

certificatesResolvers:

le:

acme:

dnsChallenge:

provider: ...

propagation:

disableChecks: true

delayBeforeChecks: 30s

Not checking for propagation of course has a chance that the record didn’t propagate during the delay time, so the delay time should be adjusted accordingly. I’m using Cloudflare as my public DNS host, and since my network’s resolvers also forward to Cloudflare, the record is shown to propagate very quickly. Your mileage may vary.